Danielle Dutton

Danielle Dutton is the author of Attempts at a Life, SPRAWL (a finalist for the 2011 Believer Book Award), and Margaret the First, named a best book of the year by The Wall Street Journal, Vox, Lit Hub, St. Louis Magazine, etc., and winner of a 2016 Independent Publishers Book Awards gold medal in historical fiction. She also wrote the texts for Richard Kraft’s Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera. Her writing has appeared in Harper’s, BOMB, Fence, Noon, The Paris Review, The White Review, etc. In 2009 she co-founded the acclaimed feminist press Dorothy, a publishing project. The press is named for Dutton’s great aunt, a librarian who drove a bookmobile through the backroads of Southern California, delivering books to rural desert communities. Born and raised in California, Dutton now lives in Missouri with her husband and son. She teaches literature and writing at Washington University in St. Louis.

Danielle Dutton

Danielle Dutton is the author of Attempts at a Life, SPRAWL (a finalist for the 2011 Believer Book Award), and Margaret the First, named a best book of the year by The Wall Street Journal, Vox, Lit Hub, St. Louis Magazine, etc., and winner of a 2016 Independent Publishers Book Awards gold medal in historical fiction. She also wrote the texts for Richard Kraft’s Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera. Her writing has appeared in Harper’s, BOMB, Fence, Noon, The Paris Review, The White Review, etc. In 2009 she co-founded the acclaimed feminist press Dorothy, a publishing project. The press is named for Dutton’s great aunt, a librarian who drove a bookmobile through the backroads of Southern California, delivering books to rural desert communities. Born and raised in California, Dutton now lives in Missouri with her husband and son. She teaches literature and writing at Washington University in St. Louis.

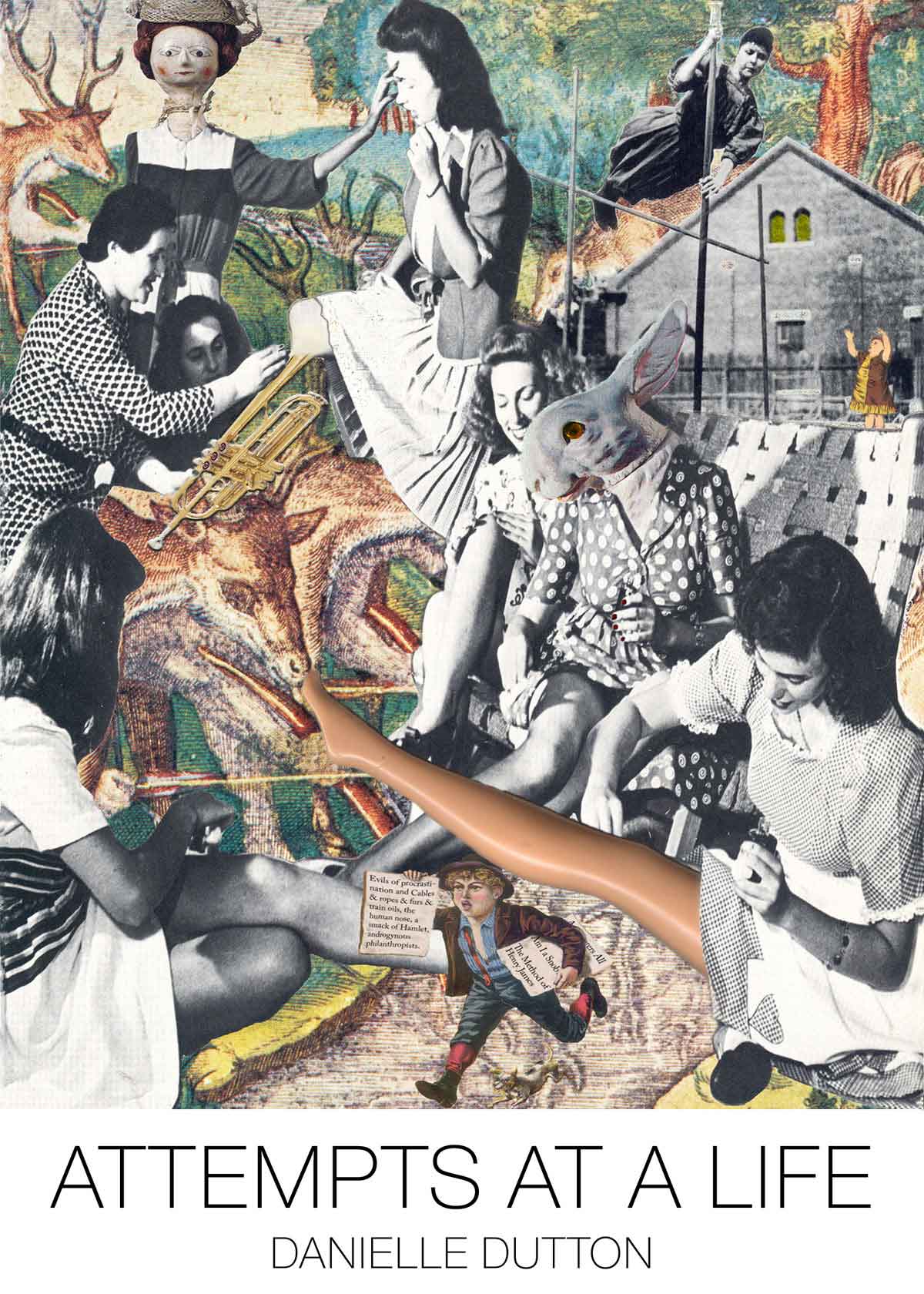

Attempts at a Life

by Danielle Dutton

A Small Press Distribution Bestseller

Featured in “Ten Great Titles from Underground Presses” from Time Out New York

Fiction. Short stories. 90 pages. Paperback. 2007

Operating somewhere between fiction and poetry, biography and theory, the pieces in Attempts at a Life, though nominally stories, might indeed be thought of as “attempts.” They do what lively stories do best, creating worlds of possibility, worlds filled with surprises, but rather than bring these worlds to some sort of neat conclusion, they constantly push out towards something new. In “S&M,” a marriage suffers from “the words you were always missing: sky, loft, music, dogs, pipes, puppets, war.” In “Mary Carmichael,” a woman with a pair of scissors and the need to “cut out her insatiable desire” slices “a veiled hat from a fern in a pot” and “a river out of a postbox.” This is writing in which the imagination (both writer’s and reader’s) is capable of producing almost anything at any moment, from a shiny penny to an alien metropolis, a burning village to a bright green bird.

Danielle Dutton executes expert, miniscule language slips that make us slide down the surface of her narratives like raindrops streaking the windows of the last un-gentrified house in an old Victorian neighborhood. . . . An important new literary voice. (Peter Connors, Rain Taxi) In Dutton’s appropriation of the genre’s hallmarks of tone and syntax, she recontextualizes the gothic setting. The ruined estate becomes language itself. Language is the setting which allows us to dream. And as the surrealist uses of Gothic elements remind, if we can dream in this way, we might trespass into the unfamiliar, and in so doing uncover more poignant ways to attempt life. As the drama inherent within the book’s title suggests, there is a way that Dutton’s appropriations project the human drama onto the stage of the book. It’s serious, but as many dramatists celebrate: comedy orbits a dark sun. Which is to say, this is also a very funny book. (Selah Saterstrom, American Book Review) Danielle Dutton’s stories remind me of those alluring puzzles where the pool is overflowing and emptying at the same time. Dutton’s answer? That the self is a rush of the languages of storytelling and moments of helpless intimacy, and she recalculates the lives of her numerous heroines to assert the busy and the broken. (Robert Glück) Danielle Dutton writes with a deft explosiveness that craters the page with stunning, unsettling precision. Here “car lights like licorice whips slick the road outside the window,” there “the puffed-thumb Emma person” sways and falls, and everywhere “the firelight is orange against the midnight of the ocean.” Her marvelous, generous Attempts at a Life proves that, like Gertrude Stein, she knows how to be “at once talking and listening.” (Laird Hunt)

Danielle Dutton executes expert, miniscule language slips that make us slide down the surface of her narratives like raindrops streaking the windows of the last un-gentrified house in an old Victorian neighborhood. . . . An important new literary voice. (Peter Connors, Rain Taxi) In Dutton’s appropriation of the genre’s hallmarks of tone and syntax, she recontextualizes the gothic setting. The ruined estate becomes language itself. Language is the setting which allows us to dream. And as the surrealist uses of Gothic elements remind, if we can dream in this way, we might trespass into the unfamiliar, and in so doing uncover more poignant ways to attempt life. As the drama inherent within the book’s title suggests, there is a way that Dutton’s appropriations project the human drama onto the stage of the book. It’s serious, but as many dramatists celebrate: comedy orbits a dark sun. Which is to say, this is also a very funny book. (Selah Saterstrom, American Book Review) Danielle Dutton’s stories remind me of those alluring puzzles where the pool is overflowing and emptying at the same time. Dutton’s answer? That the self is a rush of the languages of storytelling and moments of helpless intimacy, and she recalculates the lives of her numerous heroines to assert the busy and the broken. (Robert Glück) Danielle Dutton writes with a deft explosiveness that craters the page with stunning, unsettling precision. Here “car lights like licorice whips slick the road outside the window,” there “the puffed-thumb Emma person” sways and falls, and everywhere “the firelight is orange against the midnight of the ocean.” Her marvelous, generous Attempts at a Life proves that, like Gertrude Stein, she knows how to be “at once talking and listening.” (Laird Hunt)