Mariko Nagai

Having grown up in Europe and America, Mariko Nagai studied English with a concentration in poetry at the New York University where she was the Erich Maria Remarque Fellow. She has received Pushcart Prizes both in poetry and fiction and has received fellowships from the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center, UNESCO-Aschberg Bursaries for the Arts, Akademie Schloss Solitude, Yaddo, and Hawthornden International Writers Retreat, among others. Her works have appeared in Pushcart Prize anthologies, Best Pushcart Poetry of the Last 30 Years, and in numerous literary journals including New Letters, The Gettysburg Review, Southern Review, and Asia Literary Review. She is the author of Histories of Bodies: Poems (Red Hen Press, 2007), Georgic: Stories (BkMk Press/University of Missouri Kansas City, 2010), Dust of Eden: A Novel (Albert Whitman & Co, 2014), Irradiated Cities (winner of 2015 NOS Award, Les Figues, 2017), Under the Broken Sky (MacMillan/Henry Holt / Christy Ottaviano Books, 2019), and the forthcoming Body of Empire (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2021) and The Sword of Yesterday (Little, Brown / Christy Ottaviano, 2023). Her work has been translated into Vietnamese, French, Chinese, Romanian, Bulgarian, and German. She currently lives in Tokyo and is Professor of Creative Writing and Japanese Literature at Temple University Japan Campus.

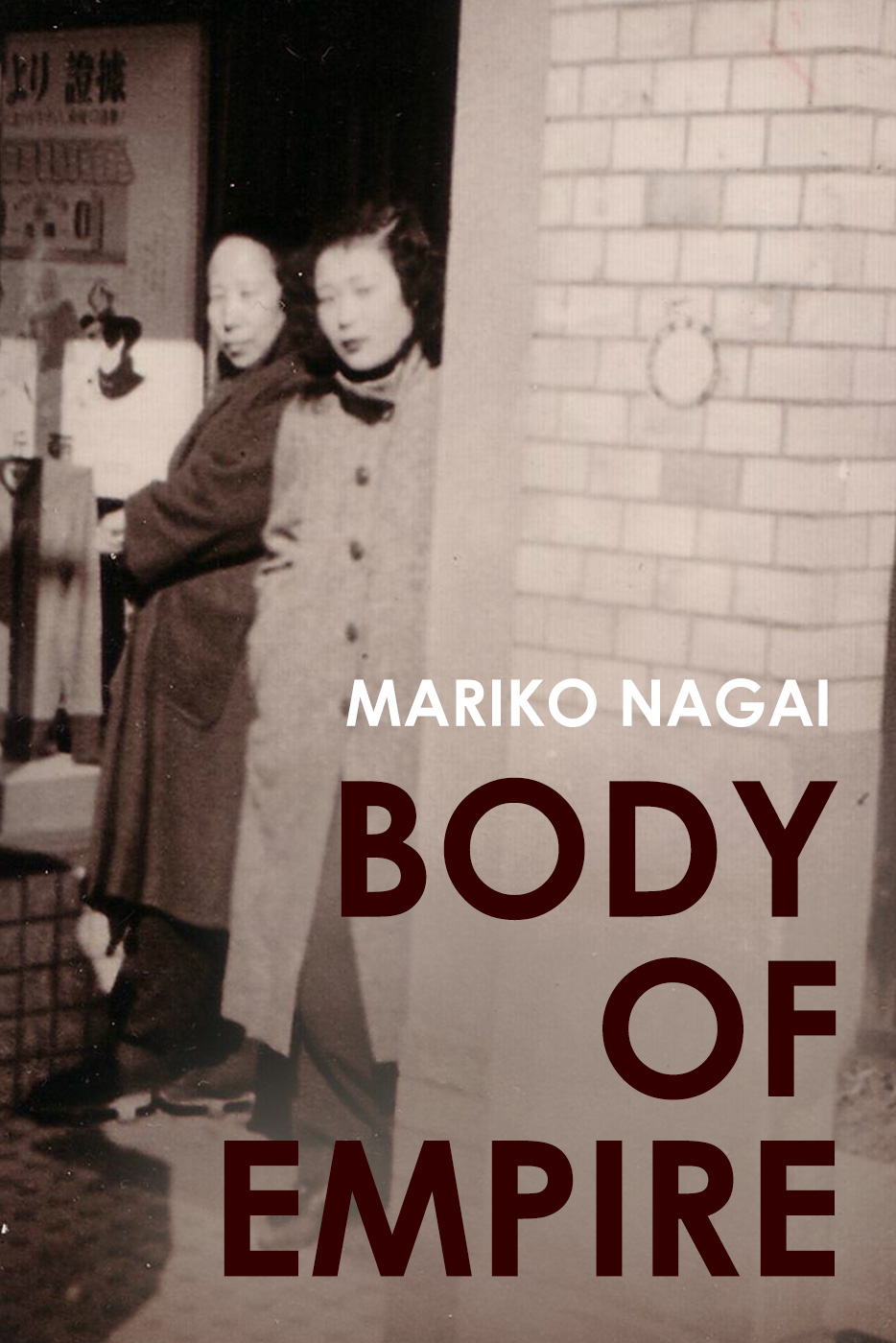

Body of Empire

by Mariko Nagai

Co-winner of the Tarpaulin Sky Book Award

Nonfiction

272 pages. Paperback. 2022

Weaving historical documents, photographs, and first-hand accounts against a background of nationalism and war, Body of Empire explores the lives of Japanese sex workers – both government-sanctioned and freelance – between 1868 and 1953. Some hid in the bottom of ships heading toward Shanghai or Hong Kong. Some were auctioned off to Singapore, Manila, Borneo, Thursday Island, Rangoon, and Bombay. Some were taken from villages in Korea with a promise of a better job, even an education, then were herded into Japanese Imperial Army ships and labeled “military supply.” Some lost their families in air raids and were stranded without homes, opening their legs to the “white devil” soldiers as a last chance to survive. Karayuki-san. Rashamen. Comfort women. Special Women of RAA. Panpan. Only-san. Different names, different times, all of them women and girls whose bodies were bought and sold by men.

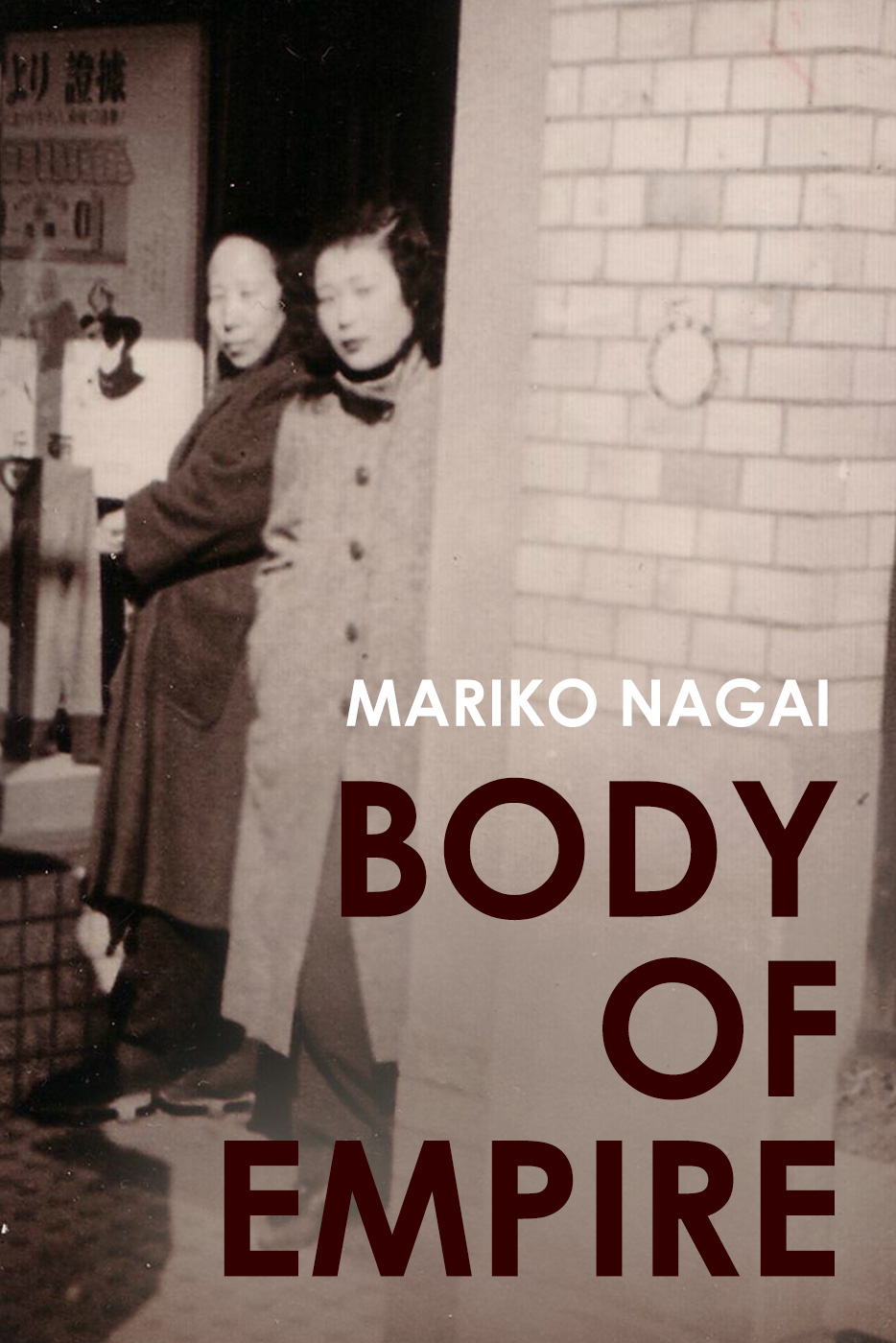

Body of Empire

by Mariko Nagai

Co-winner of the Tarpaulin Sky Book Award

Nonfiction

272 pages. Paperback. 2022

Weaving historical documents, photographs, and first-hand accounts against a background of nationalism and war, Body of Empire explores the lives of Japanese sex workers – both government-sanctioned and freelance – between 1868 and 1953. Some hid in the bottom of ships heading toward Shanghai or Hong Kong. Some were auctioned off to Singapore, Manila, Borneo, Thursday Island, Rangoon, and Bombay. Some were taken from villages in Korea with a promise of a better job, even an education, then were herded into Japanese Imperial Army ships and labeled “military supply.” Some lost their families in air raids and were stranded without homes, opening their legs to the “white devil” soldiers as a last chance to survive. Karayuki-san. Rashamen. Comfort women. Special Women of RAA. Panpan. Only-san. Different names, different times, all of them women and girls whose bodies were bought and sold by men.

Someone (an old man) once said that the first casualty of war is truth. Through Body of Empire‘s painstaking disinterment and resurrection of the actual truth of war, Mariko Nagai suggests—or rather demands—a greater and more grim reality: that the first casualty of war—and also the last, and longest suffering—are women. Nagai illuminates, through the insidious fog of history, the inner and outer lives—the dreams, the nightmares, the subjection, the subjectivity, and the unimaginable will—of nearly one hundred years of women, and in doing so, has committed an astonishing act of counter-erasure. (Brandon Shimoda) In Body of Empire, Mariko Nagai fearlessly and irrepressibly exposes the objectification, violation and consumption of women’s bodies from the late 19th century to post-WWII. Nagai’s indelible reclamation of the Japanese sex worker humanizes the courageous women who were rendered into commodities and consigned to history’s footnotes. The book’s powerful narrative of courage and survival traces legalized, volitional and forced prostitution against a backdrop of patriarchy and imperialism. In colonial outposts, frontier towns and domestically, Nagai uncovers women who have been lost or silenced. This extraordinary bricolage includes numerous historical documents, such as photographs, postcards, interviews, lists, statistics, surveys, journalism and memoir. Nagai writes, “No one wants to be doing this, but women do. People do everything and anything to survive.” History lives in the body, and Body of Empire reminds us that international politics is gendered as it recovers the women who laid down their bodies for their country. (Cassandra Atherton) Mariko Nagai’s Body of Empire begins as an examination of the role of Japanese prostitution in the rise of Imperial Japan, where women, sold by their own families or tricked under the guise of national service, are conscripted as nothing but bodies and barely even that. Male soldiers, supplied with “Assault Number One,” government–issued condoms distributed in the name of the Emperor on behalf of Japan’s expanding power and might, invade one country after the next. Chinese women, Burmese women, Korean women are churned through the gears of imperial ambition. But when America occupies a defeated Japan, it becomes clear that Nagai’s investigation is not only or mainly about Japan itself but rather more broadly about empire and the gendered damage it wreaks. When Japanese men watch their American counterparts take their places in a war on women’s bodies it becomes clear that women, regardless of country, live in an occupied state. A harrowing, essential work, Body of Empire uses first person accounts of the men and women of war to show how men fighting men reduce woman after woman to nothing more than sacrificial bodies, never meant to speak for themselves, let alone hope or dream, or god forbid, to act, decide, and govern. (David Naimon) A haunted and inspired work, Body of Empire interrogates the ways in which women’s bodies have been forced to hold the ambitions and desires of empire, and the need to unbind these maps from the flesh. What maps you?, one might ask, so easily forgetting that the map is not the territory, and that a woman’s body should not be a container for trauma. In the collaborative conjuration of women’s wounds through these brilliant & devastating texts, might we be able to extract these calcifications and bring to light / in light in order to facilitate a gradual healing? (Janice Lee)

Someone (an old man) once said that the first casualty of war is truth. Through Body of Empire‘s painstaking disinterment and resurrection of the actual truth of war, Mariko Nagai suggests—or rather demands—a greater and more grim reality: that the first casualty of war—and also the last, and longest suffering—are women. Nagai illuminates, through the insidious fog of history, the inner and outer lives—the dreams, the nightmares, the subjection, the subjectivity, and the unimaginable will—of nearly one hundred years of women, and in doing so, has committed an astonishing act of counter-erasure. (Brandon Shimoda) In Body of Empire, Mariko Nagai fearlessly and irrepressibly exposes the objectification, violation and consumption of women’s bodies from the late 19th century to post-WWII. Nagai’s indelible reclamation of the Japanese sex worker humanizes the courageous women who were rendered into commodities and consigned to history’s footnotes. The book’s powerful narrative of courage and survival traces legalized, volitional and forced prostitution against a backdrop of patriarchy and imperialism. In colonial outposts, frontier towns and domestically, Nagai uncovers women who have been lost or silenced. This extraordinary bricolage includes numerous historical documents, such as photographs, postcards, interviews, lists, statistics, surveys, journalism and memoir. Nagai writes, “No one wants to be doing this, but women do. People do everything and anything to survive.” History lives in the body, and Body of Empire reminds us that international politics is gendered as it recovers the women who laid down their bodies for their country. (Cassandra Atherton) Mariko Nagai’s Body of Empire begins as an examination of the role of Japanese prostitution in the rise of Imperial Japan, where women, sold by their own families or tricked under the guise of national service, are conscripted as nothing but bodies and barely even that. Male soldiers, supplied with “Assault Number One,” government–issued condoms distributed in the name of the Emperor on behalf of Japan’s expanding power and might, invade one country after the next. Chinese women, Burmese women, Korean women are churned through the gears of imperial ambition. But when America occupies a defeated Japan, it becomes clear that Nagai’s investigation is not only or mainly about Japan itself but rather more broadly about empire and the gendered damage it wreaks. When Japanese men watch their American counterparts take their places in a war on women’s bodies it becomes clear that women, regardless of country, live in an occupied state. A harrowing, essential work, Body of Empire uses first person accounts of the men and women of war to show how men fighting men reduce woman after woman to nothing more than sacrificial bodies, never meant to speak for themselves, let alone hope or dream, or god forbid, to act, decide, and govern. (David Naimon) A haunted and inspired work, Body of Empire interrogates the ways in which women’s bodies have been forced to hold the ambitions and desires of empire, and the need to unbind these maps from the flesh. What maps you?, one might ask, so easily forgetting that the map is not the territory, and that a woman’s body should not be a container for trauma. In the collaborative conjuration of women’s wounds through these brilliant & devastating texts, might we be able to extract these calcifications and bring to light / in light in order to facilitate a gradual healing? (Janice Lee)