|

IV

Dream of the Marten

(1925)

In the dream I am walking along a headland. Here the rocks have created an odd sort of pass. I wander until I reach a large modern villa with terrace and gazebo adorned with grapevines. It seemed to me in the moonlight like backstage of the Paris Opera. Wanting to spend the night in the gazebo, I climb over the wall. My drowsing was disturbed by the shutters opening on the first floor, which emitted a light the crown of a lush palm engulfed. A woman leaned out of the window. I couldn’t determine her age as she appeared to me as a silhouette. Her hair struck me as peculiar: it was done up in an outmoded bun. Then I discovered it was white, and as she moved I could see the glitter of pearls sewn onto ribbons plaited into her hair. The lady leaned out the window and quietly called out: “I’ll redeem the box when the night is over.” From the top of the palm above me I suddenly heard a melody that reminded me of an old ditty. When I looked to see who was singing it, I saw a giant orangutan playing a fiddle. He had a ruby red box with an odd handle in the shape of a child’s hand hanging from a strap. On the branch of a tree standing near the palm sat a large horse, its head erect as if an illustration in an old book on natural history, as if fascinated by the singing. It had been flayed, and the skin and hairs on its neck gave way to raw meat, which was larded with bacon fat like a hare ready for roasting.

|

|

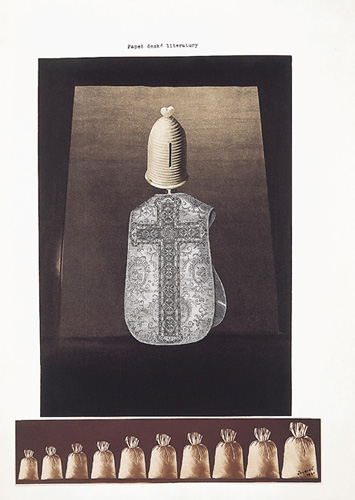

"The Pope

of Czech Literature"

VII

Dream of Vítezslav Nezval

(February 15, 1927)

. . . I’m telling my mother and father about something that happened to me in Paris. Father has to go to Berlin for some business reason — — — I’m looking for someone (I don’t want to say it’s Toyen) in the Les Halles district. I come to a house, open the door — — narrow — — I enter the parlor — — no one — — first floor, no one — — — darkness — — I go upstairs, no one — — I cough — — I call out “hello” — — no one — — when I’m on the third floor I’m overcome by horror and fly downstairs — — no one — — A blank — — — — I don’t know — — — — — in front of the house is a small square (The Moor café), flagstones, about which I say: large as a room. Nezval’s lying in a chest, a coffin — — Backing up (I’m leaving the house with someone) a man says: he was a fat one, he liked his booze — — Nezval lying in the small coffin, his legs tucked up; someone takes a leg and breaks it off and then the other and lays them down — — — the shoe soles in his armpits — — — — — Teige somehow appears — — — before that someone, evidently the man I had left the house with, was looking through Nezval’s pants pockets; it isn’t there, but he finds it in his wallet. Nezval seems alive but continues to lie there, though his hands refuse to give up the wallet. Teige says we need to take it from him, that he shouldn’t be buried with money. At this point I wake up.

|

|

XI

Dream of the Tattooed Infant

(June 3, 1929)

I am with Jindřich Honzl at a dance at the Budiš Inn in Verměřovice. We’re enjoying ourselves. There is a plot against us. We want to secretly slip away. At night we flee through the garden, through fields of beet and potato. We hide in a thicket in the woods.

Honzl and I are bound to poles, or to beams in the middle of a barn or a gym. Around us in an orgy of dance are ten- to twelve-year-old TATTOOED BOYS. They are armed with sticks and make threatening gestures at us. In their midst we also see an infant TATTOOED WITH PORNOGRAPHIC images.

|

|

XIII

Dream of Father

(night of October 15-16, 1931, Kremencová Street, Prague)

. . . I am at our farm in Čermná, in what we call the front room. I am looking for a legal document or letter in an old writing desk. I am alone in the house and this feeling of total isolation makes me uncomfortable. I am afraid, a form of the fear I used to have as a child when I had to go alone to the cellar or attic. Suddenly the door opens and Father comes in. At this moment I feel much better. A sigh and the sensation of suffocating leaves me. We both look for receipts from the sale of hay. We argue and our arguing becomes a brawl. I see my father grow pale, his left arm raised, holding a chair over my head, ready to strike me with it. I swerve out the way and the chair misses, its momentum carrying it to the floor. It occurs to me to leave to bring this distasteful scene to an end. I tell myself: Father is already an old man. I go to the door but glance back. I see Father standing on one leg on the backrest of a chair, his other leg balancing in the air. He’s stiff and pale, practically white. He’s wearing a wedding frock and over it a white gown, a blazing candle on his left shoulder. He seems mute. His shoulders move convulsively, jerkily, as if he were racked by sobbing. Yet the look he gives me is as vicious as it was a moment ago, and I see in his eyes that he would like to strike me while being unable to do so. Suddenly, I don’t know how, a second chair appears under his groping leg. I see him straddle on two chair backs. They seem to be attached to his legs and all at once he starts to come after me, taking strides several meters long. But he is still stiff and it’s not his blows I run away from, since I know he’s incapable of hitting me, but from his apparition. He has caught me off guard, and before I manage to run out the door he chases me around the room a few times. Then it occurs to me that he’s been dead a long time and that what’s pursuing me is his corpse. This doubles my horror. I run down a long hallway, across the yard below the stable and barn and into the fields. But my father on his monstrous stilts is still on my heels. Under an oak the ground gives way beneath me and I sink into a slough. When I am up to my chest in the mire I think that this is the end of me and in any moment the mud will close over my head. I feel an intense hatred for my father, but am comforted by the thought that he must drown in the mud with me. I look back and cannot find him in the whole landscape. He’s vanished. I discover that a large cork float similar to a millstone has appeared around my neck. I feel good. I know that I’m saved. I swim. Yet I’m certain that Father hasn’t drowned either, and I’m terrified that in my next dream he’ll pursue me again on those chairs.

|

|

XV

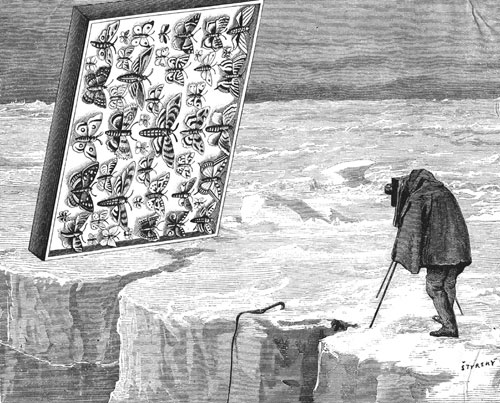

Dream of Butterflies

(1932 — nearly the same dream in 1937)

I’m lying on a grassy balk (in Čermná?). Suddenly I see butterflies landing on the flowers around me (cabbage whites), their tiny bodies pierced by long pins as if they had flown away from a collection. Before I could even realize it, an entire swarm suddenly flew to me and landed on my hands and face, until they completely covered me, sticking me with their pins. I woke up in pain, and also: they would have SUFFOCATED me.

|

|

XVII

Dream of Jaroslav Seifert

(night of July 23-24, 1934, Hotel Prokop, Špicák na Šumave)

Dusk. We’re walking through a terrifying forest. We come to a quarry through a tunnel; there is no exit. It is night, but there is moonlight. A child whose age and sex I cannot determine is running and jumping around the cliff. I’m extremely worried that the child will no longer be able to walk. He howls that he’s thirsty. He’s Jaroslav Seifert’s child. Ura brings water in one of those square glasses countryfolk use for drinking wine. Seifert is furious. He says children should always have fruit juice in their water. He catches the kid and holds him between his knees in the same way one holds a goose when feeding it. With one swipe he lops off the head. Then he comes to us, squeezing the child’s head in his hands. I find the whole scene comical. Seifert’s gestures remind me of a salon magician. He shows us a wrinkled lemon. Ura holds out the glass and tells him to give the lemon a good squeeze. I regret that it’s night and I cannot photograph Seifert for my album of Czech poets.

All texts and images by Jindřich Štyrský.

Translated from the Czech by Jed Slast.

|

|

The dream journal texts and images are from Sny (1925-1940) (Prague: Odeon, 1967).

The volume was originally prepared for publication by Štyrský in 1940, but could not be put out during the German occupation. When Štyrský died in 1942 his manuscripts came into Toyen’s care, and she was responsible for eventually getting them published. The English translation of the two volumes together is forthcoming from Twisted Spoon Press under the tentative title Dreamverse. The dream journal texts and images are from Sny (1925-1940) (Prague: Odeon, 1967).

The volume was originally prepared for publication by Štyrský in 1940, but could not be put out during the German occupation. When Štyrský died in 1942 his manuscripts came into Toyen’s care, and she was responsible for eventually getting them published. The English translation of the two volumes together is forthcoming from Twisted Spoon Press under the tentative title Dreamverse.

Jindřich Štyrský (1899,

Čermná–1942, Prague) was a painter, poet, editor, photographer, and

collagist. His outstanding and varied oeuvre included numerous book covers and

illustrations (he was one of the first to illustrate Maldoror). He also wrote

studies of both Rimbaud and Marquis de Sade. He became a member of Devětsil

in 1923, participating in their group exhibitions. Between 1928-29, he was

director of the group’s drama wing, the “Liberated Theater,” where he

collaborated with Nezval (the dance performance of his poetry collection Alphabet)

among others. Štyrský was also an active editor. In addition to his Edition 69

series, where his Emilie Comes to Me in a Dream appears as volume 6, he

edited the Erotic Review, which he launched in 1930, and Odeon, where

many of his shorter texts appeared. He was a founding member of The Surrealist

Group of Czechoslovakia.

|

|