The Morning After

Email to an American friend living in Canada, composed in the immediate aftermath of the US election in the still-dark, early morning hours.

**&!#&%##!!!^^!!@##!!

I should use emoticons if I could, but I think you get the drift.

You recall my saying at lunch yesterday that I felt the need to write something about the upcoming vote, that I felt as if we were on the brink, the cusp, of something. I did—in the wee hours of the morning of November 8th— in bed, so notes really. After having watched the SNL election special consolidating the metamorphosis of the election process into the politics of spectacle.

Written at the spectre of a Trump election – November 8th

I think of the gutter — summing up the tone of the election, gutter politics. My mind turns to how historically this has been projected on to Blacks as being the bearers of impropriety, yet so much at the heart of Western society has been scandalous and improper, if not downright obscene. Yet so little sticks. The polls all say that Hillary Clinton will win, but the polls have been wrong before— witness Brexit—and even if she does win, Trump has won the hearts and minds of the American public that is the raw underbelly of a bloated, imperialist state. He has given new meaning to the expression: Anybody can become president of the United States—anybody as in serial harasser and predator of women; as in known racist supported by the KKK; as in a shady dealer, snake oil salesman; as in confirmed liar. Anybody! But a competent, experienced, intelligent woman. (Was amused to hear Trevor Noah say the same thing a few hours ago on his show.)

America’s greatness has been based on exploitation of the world’s people and their resources, beginning with its indigenous populations, continuing on over into the enslavement of Africans, and over into the Monroe doctrine that held the southern hemisphere in its vice grip and over and over…. The American dream has been our nightmare.

On my walk earlier today, or yesterday rather, I listened as Michael Moore on Democracy Now talked about a movie he made addressing Trumpland about their wish to use their vote to get back at those whom they feel have ignored them. He talked about the short-lived satisfaction they’ll get from voting in anger, and I recall the alternative school my children attended, and how a group of us parents attempted to increase the diversity of the student body. Rather than let that happen, the white parents opposed to those changes opted to close the school. I recall how the Portuguese, at the end of their colonial regimes in Mozambique and Angola, destroyed as much as they could in those countries, rather than leave an infrastructure for the incoming regimes. The people whom they had exploited for centuries should have nothing of what they helped to produce. For some reason as I listened to Moore’s impassioned plea to the people, reminding them of Brexit and the fallout, my mind turned to those events —one very personal, the education of my children, the other large and very much removed—the end of Portuguese colonialism, because in a flash I have the sense that those who see Trump as their saviour would rather destroy the country, as they know it, than have it remain in the hands of those whom they believe they must take it back from. The rage—what is a Black man doing in our Whitehouse?—and the commitment to a belief in the rightness of white supremacy that provides them a privilege are so total and totalising that they would rather see the US destroyed than let “them” have it.

Can we thank Trump for showing us the murky, abysmal depths that a politics of salvation in the media-saturated digital age can engender? Can we thank him for illustrating the teflon quality of whiteness and revealing the extent to which different sets of rules exist for men and for women; for Black and for white people? Could, for instance, a Black man have the c.v. of deplorable activities that Trump has and be a serious contender for President? Can we thank him for the insights he provided into the make-America-great-again way of life, at the core of which is hatred of the Other? Can we thank him for showing us the depth of the resentment?

In these small, lonely hours of a morning before the day after I ask myself

—what will it look like?

—will we survive?

—how much harder will it be forAfrican Americans, Muslims, Indigenous people, women, LGBTQ2 communities, the disabled — indeed, for everyone who is not white, male and straight.

Perhaps, I should thank him for showing us the gap between the bottom and those who adhere to some semblance of civility.

Written after the vote in the small, beginning hours of the aftermath on November 10th

There is much to admire in the US, which, at the end of the day, much like every other society is a human, and therefore flawed, attempt to allow that humanity to flourish within a set of rules. Too often these are imposed from above, but especially in the case of the US are challenged over and over again, by Black people, women, gays, trans people, the poor, and many, many others, as they scrabble and lurch towards a place where the individual in all her difference and sameness can exist and flourish with dignity. Like it or not, the struggles, successes and failures there affect struggles in other parts of the world. Donald Trump at the helm of the most powerful state in the world just made the distance between the longed-for ideals and a brute reality that much wider. And I want to weep.

Three days later

I am astounded at how all those who have been scapegoated by Trump are expected to forget the hurtful words and move on. Predatory sexual behaviour towards women must be forgotten; misogyny viewed as a thing of the past; barefaced lying chalked up to campaign shenanigans; racist views and words overlooked.

I am astounded at how quickly the markets have rebounded. Even Brexit created a longer financial period of turmoil in the UK.

I am further astounded by how easily the explanatory script for Trump’s election is the ignoring of the plight of those who now inhabit the rust belts of the US—the white working class who have been dispossessed by the workings of capital, of which Trump is a major player. I sympathise and have compassion, but where is the understanding and compassion for the historically dispossessed, like African Americans and Indigenous people, marginalised and forgotten (except as objects of fear and threat) far longer than their white brothers and sisters of the rust belt? There has been no saviour for them. Not even Obama.

I want to turn my face away from the horror of it all. I do not live in the US, so why should it matter? Do I really have any authority to speak, not being a US citizen? I do, because the US as an exemplar casts a long shadow: here in Canada, for instance, we have politicians who have commended Trump on his win and wish to emulate him; in France and other European countries Trump’s script is welcome to many right wing politicians. What are we to do? My mind turns to Simone Weil, philosopher and passionate advocate for the poor and the broken, who was of the opinion that hunger presupposed the existence of bread. Similarly, I believe, the keen hunger for justice and equality among so many of us presuppose their existence and, in the words of Sweet Honey in the Rock, “we who believe in freedom cannot rest,” knowing that as Martin Luther King said, “the arc of the moral universe (may be) long but it bends towards justice.” Always.

x

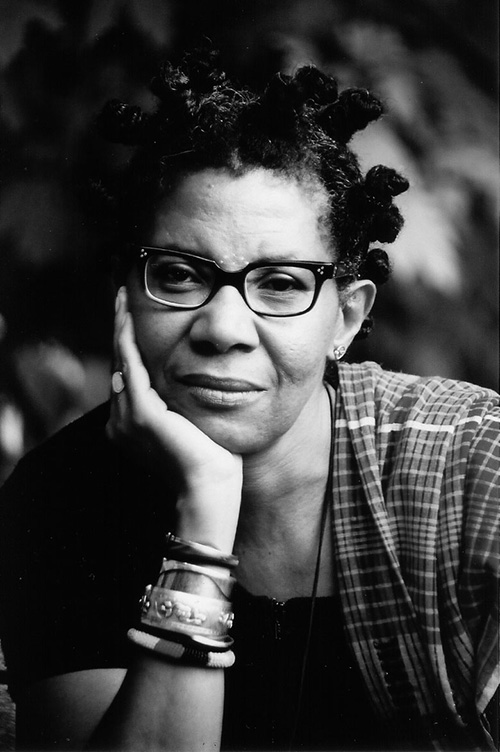

M. NourbeSe Philip is an unembedded poet, essayist, novelist, playwright and former lawyer who lives in the space-time of the City of Toronto. She is a Fellow of the Guggenheim, and Rockefeller (Bellagio) Foundations and the MacDowell Colony. She is the recipient of many awards including the Casa de las Americas prize (Cuba). Among her best known published works are: She Tries Her Tongue; Her Silence Softly Breaks, Looking for Livingstone: An Odyssey of Silence, and Harriet’s Daughter, a young adult novel. Philip’s most recent work is Zong!, a genre-breaking poem, which engages with ideas of the law, history and memory as they relate to the transatlantic slave trade.

M. NourbeSe Philip is an unembedded poet, essayist, novelist, playwright and former lawyer who lives in the space-time of the City of Toronto. She is a Fellow of the Guggenheim, and Rockefeller (Bellagio) Foundations and the MacDowell Colony. She is the recipient of many awards including the Casa de las Americas prize (Cuba). Among her best known published works are: She Tries Her Tongue; Her Silence Softly Breaks, Looking for Livingstone: An Odyssey of Silence, and Harriet’s Daughter, a young adult novel. Philip’s most recent work is Zong!, a genre-breaking poem, which engages with ideas of the law, history and memory as they relate to the transatlantic slave trade.