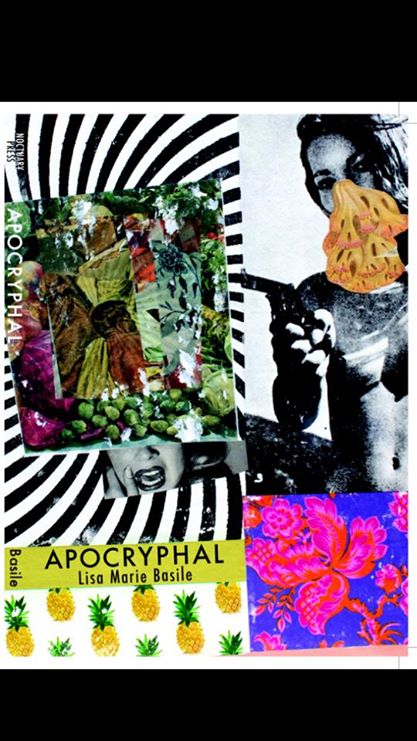

APOCRYPHAL

LISA MARIE BASILE

Paperback, 100 pages

Noctuary Press, 2014

$14

Review by Lisa A. Flowers

I am in 1967 Balenciaga. because in me there is an inauthenticity hoping for spectator [to be seen is to be real] & the speckled light of dusk is slicing the excess of me. what is left is this venom-bodied apparition you will fuck hard and hardly fuck. I am not a skinny girl I will destroy you

So ends a passage in Lisa Marie Basile’s Apocryphal, a book whose images gleam like jewels poured down a long black hole. One thinks of the heroine in Grimm’s The Three Little Men in the Wood, who was blessed with having gold pieces fall from her mouth every time she spoke, transforming her from poverty to great riches. This is an apt analogy for whatever darkness Apocryphal’s protagonist is trying to purge: an alchemizing of speech into redemption.

Not to give the impression that the book—Basile’s first full-length collection—is a primarily dark work. It is, on the contrary, set in high summer as a way of life, as it is in tropical climates—inexorable, without transience. Images of lush flowers, birds, and ice cream roll out. But the subtext is this:

I was born bad because she was born for pain.

chianti runs down her legs as a barber shop wheel spinning on a bright day.

Shift shot to a batch of sunbleached family photographs from the 1960s, their Kodak vibrancy faded into whatever life remains of the smiling relatives leaning against one of the many cars—Pontiacs, Cadillacs—that populate the book. The autos are as haunted as Basile’s speaker—by the virginity surrendered in them, by the men polishing and tending to them, like Kenneth Anger’s Kustom Kar Kommandos filmed from behind a veil of tears. We see a girl as the cosmetic of her own body, placed on her own vanity table, her whole “lifetime at the bottom of a Givenchy/compressed into a small golden tube.” We see her seducing boys in diaphanous nightgowns. (When Basile writes, “my father, of my fathers, my fulcrum: here goes my life, here goes my dress,” the raiment she speaks of is the body, mortality itself). The uncontrollable cascade of beautiful language is worthy of Octavio Paz and Marosa di Giorgio. (Basile even pens a letter to the ghost of di Giorgio that reads, in part: “I knew it was too late to chase you, you had gone, and I was left at the vanity mirror with my legs open hoping the city would understand: I don’t mean to sexualize you or our world”).

In Apocryphal, that sentiment is reversed into “love letters with the mouth un-posted.” The unmistakably feminine voice is somewhat reminiscent of Edna St. Vincent Millay, but its rolling chaos is not the stuff of form-restricted old-fashioned poetry, and sometimes its crudeness is profoundly powerful in its feminist anger, exploding in a rage that drops us, like shattered family heirlooms, at the end of tumbling, electrifying passages:

let me really set the scene for you:

in youth I was so beautiful whole houses

shut their mouths

when I came, barefoot, to stand on porches

dropping to my knees at the window

to watch my father & Sofia recklessly

their polaroid pornography

on that plastic couch…

the only thing the body knows of desire

is that it stands next to its surroundings.

**

so beautiful that my hair unbraids itself, unraveling

as stray pearls on the nightstand

which roll eventually

to land in your lap

& look up at you

as a girl gagging on cock.

Sofia may be Sophia, wisdom of God. But who can really tell what this means? “The symbol ought not speak when a girl should”, Basile writes—lines that themselves sum up Apocryphal’s enigma.

—–

In Apocryphal, water is everywhere (“the truth is/I sprawl out across the marina until I become the marina”). But the speaker is disseminated throughout earth, air, and fire just as much, and Apocryphal is confession that has escaped being confession by incarnating itself in nature. The poetry itself, in fact, seems to have escaped its own body, just as (through the very act of being written) it has already escaped Basile’s:

I wear the both of us, as two diamond hoops in my ears. the skin is stretching all over the place, my hands are the hives, & I smell of high valley fire. o, it is very young of me to spill myself like this, a pearl necklace snapped off by a drunk

“No one remembers children,” writes Basile. “I sat with my knees bent and skinny./I ate from a can./I found a private way to feel beautiful.”What can one say to a passage like the following (which, of course, is not so much about youth as it is about mortality itself)–that lays itself on the line so hand-wringingly, so gorgeously? To paraphrase Randall Jarrell about Walt Whitman, “here [Basile} has reached—as great poets always reach—a point where criticism seems not only unnecessary, but absurd”:

because they are young

they must be alive,

must be, as time must be preoccupied

with measurement,

me with my hands over my breasts,

really wringing them, plump things with pink ends,

the way they sit like flamingo flower at the window, waiting

for the sun, blushing upright, perpetually drinking

that which offers itself.

offer yourself to me. I will take anything while I am alive.

——

Time, as has been implied, is mutable in Apocryphal. “I must tell you/I grew up here, waiting out the 1960s” the speakers says “I have become many lives and many things/you can debase me/buy me flowers/let me to dry when I’m soaked.” The lack of fulfillment is implicit here, and flowers are a recurring image, as is cruelty. “Gyposphilia” is another name for Baby’s Breath, and these lines may refer to children, born or never born, and/or to the breath of life itself:

the way he actually loved twisting the gyposphilia between the bridesmaids’ legs. this was three decades ago & it is now & forever

It is perhaps not insignificant then, that, later on in the book, we encounter the murderous, almost Kafkaesque image of

a man & a briefcase, dead face down in her olive-oil thighs

——

Where does forgiveness come from? from campari. from a quiet door opening. a breeze borrowed by someone else’s spring.

Apocryphal is, to a large extent, a book about forgiveness, but it’s not clear if any ever gets granted. “I will never have to name you, & you will never name me, nor come to me/& so, you will never be on my divine leash/not here on earth nor in heaven/ where I will pass you by in Chanel and you will think, she is beautiful, but she is not mine,” Basile writes. Here we must hearken back to Plath, who wrote, in that lovely verse-play Three Women:” I remember the minute when I knew for sure./The willows were chilling./The face in the pool was beautiful, but not mine–/It had a consequential look, like everything else,/And all I could see was dangers.” However traumatized Apocryphal’s speaker may be, by fact or speculation, Basile’s poetry is a catalogue of hazards so beautifully rendered that we don’t even notice that, by book’s end, we too are at rock bottom, looking up to the sky of the world we’ve just tumbled from. The view from below is as nothing less than “wider than the sky”; or, in Apocryphal’s own words, “cinema, a conquering, validation.”

Lisa A. Flowers is a poet, critic, vocalist, the founding editor of Vulgar Marsala Press, and the author of diatomhero: religious poems. Her work has appeared in The Cortland Review, elimae, THEThe Poetry, The Collagist, Entropy, and other magazines and online journals. She is a poetry curator for Luna Luna Magazine. Raised in Los Angeles and Portland, OR, she now resides in the rugged terrain above Boulder, Colorado. Visit her here or here.